Fun Facts and Little Secrets: About the Author

From my early childhood days up until now, I’ve relished being a storyteller and had a deep love of animals and the natural world. In the rural area at the foothills of New York’s Catskill Mountains where I grew up, I was outside a lot on my own or with my sister.

Mother Nature provided most of our “toys”. We made up stories together and enacted them privately all the time. My mom was super-busy working and caring for the family, and so I attempted to get her attention by being entertaining at home, or when that failed, horrifying.

She was quite emotional and I usually got some kind of response, which was all I really wanted.

I guess when you’re a kid, they call spinning tales “telling lies” but in adult life, it’s “writing fiction”. I quickly learned truth was stranger than fiction, and began to love nonfiction as well.

As I matured, I also tried to be inspiring through my writing. To find the ray of hope after a storm; to discover the silver lining in any disaster.

I had an early start with writing. By sixth grade I was making up short stories. My teacher that year read one of these aloud to our class, but stopped quite suddenly only halfway through.

He said it obviously couldn’t have been written by a child, and discarded it. John Steinbeck was my favorite author at that time, so I’d picked up a style that was a bit dark.

This setback stopped me for a while, but by 10th grade I had a whole folder of new stories and also some essays and poems. I submitted these at school without keeping copies, and a few weeks later my English teacher told me he’d lost them all.

So that was a second delay. I didn’t get going again until I was about 25, a few years after graduating college with a science degree.

The strangest thing that ever happened to me was later that year. I’d been writing poetry nights, and at an in-person workshop I took in West Philadelphia taught by renowned poet and South African activist, Dennis Brutus, author James Baldwin walked in halfway through the class as a guest.

The small, older man was attractive, sensitive and soft spoken with great warmth. After he’d shaken hands with each of us and left, I asked, “Who’s James Baldwin?”

That I didn’t know of the iconic writer’s novels and essays or about his huge influence on other US authors horrified my classmates. I soon read all Baldwin’s novels and essays, which deeply affected me.

And then I was hooked on the idea of transforming stories into activism. Much of my writing addresses social issues of our time in one way or another.

A little-known, odd fact about me is that I prefer fruits and vegetables over all kinds of other foods simply because the sight of meat disturbs me.

This began in childhood after seeing beloved chickens disappear from the backyard and appear as a dish at the table the following day.

I love all kinds of animals, and currently have two sweet rabbits at home adopted from a local New York City animal shelter. A close friend once asked me what animal I would choose as my likeness, hinting slyly that this could reveal more of my inner life to him.

When I replied “fox,” then added “or maybe lion,” he was shocked, but he erupted in hysterical laughter shortly afterwards. He’d expected me to say some kind of gentle bird that ate only plants, he explained.

And I get it. At the time, I kept a cage-free pet cockatiel and a fruit-eating lorikeet as companions at home. But who and what we care for, aren’t necessarily the same things as who we are.

Excerpt

Genre: Nonfiction Memoir

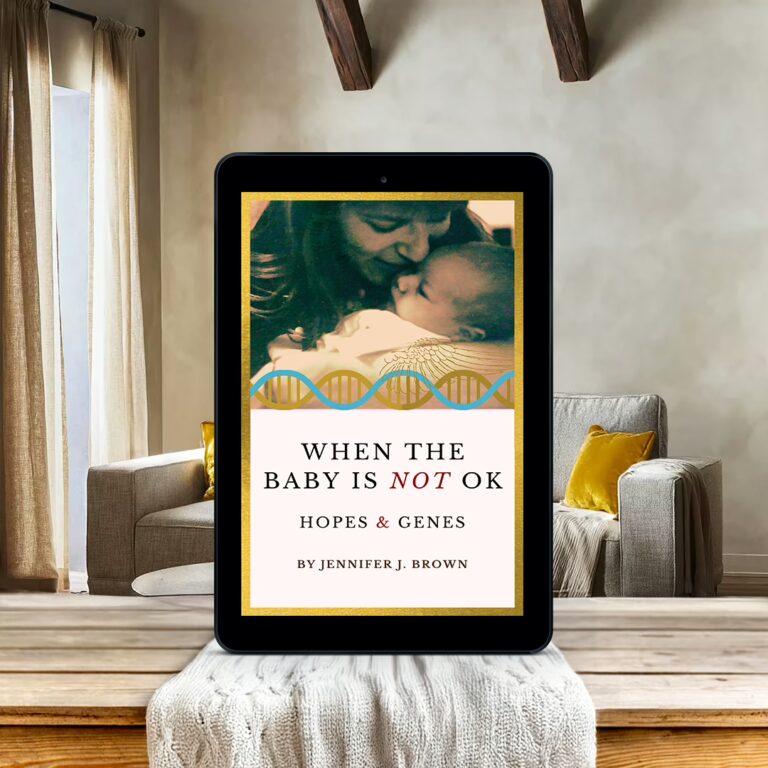

When the Baby Is Not OK: Hopes & Genes by Jennifer J. Brown, 2025

I’ve blocked out a lot regarding the hospital’s phone call that pivotal day. The brain’s neural pathways are blessedly wired to forget certain things. A version of the words does come back to me but not the sounds or pictures that make up my other memories. I can’t hear the caller’s voice in my head. Not whether they were young or old, a woman or man, kind or cruel. It went something like this.

“There’s a problem with the baby’s first blood test results from newborn screening. The baby is not OK. You’ve got to come back to the hospital. Right away. Your baby tested positive for a rare disease. It’s a genetic disorder, phenylketonuria. PKU.”

Hmm, I thought, really? What are the odds?

Abstract thinking can avoid facing difficult feelings. It’s one of the psyche’s common defense mechanisms. Somewhat effective protection from mental pain. I’m a numbers person and so those immediately raced helpfully through my mind.

Here they are. The odds are less than 1 in 10,000 that a newborn baby will have PKU in the US. True, as the caller said to me, it’s rare. And for me, personally? At the time I was studying to become a geneticist – a scientist who works with DNA, genes and those diseases that run in families. Only 1 person in 10,000 is a geneticist in the US. So that’s about as rare as a baby having PKU – but completely unrelated.

The odds of two independent things happening at the same time are small. Far smaller than either one of them happening alone. They’re the odds of one multiplied by the odds of the other. Even in my blurred postpartum state of the baby blues I knew that came to only 1 in every 100 million births. So this event of a geneticist having a baby who has PKU might happen to maybe 3 people of the nearly 300 million in the entire US population.

That certainly put things in perspective.

Is it even possible?

Yes. But so very, very unlikely.

Every thought I’d ever had in my entire life that related in any way to PKU flashed before my eyes. Like what some people say happens before the moment of death. I felt that threatened.

I couldn’t think about the promise of modern medical care for people who had PKU because I didn’t know a thing about it. Nothing about the present realities for children or adults who were actually living with PKU. Nothing about the optimism that might inspire. Nothing about the hope.

I vividly saw what I’d heard, learned and read. During my science classes I’d heard that babies were sometimes born with atypical health conditions labeled “rare diseases.” Having PKU was genetic; it ran in families.

Having genes for PKU prevented breakdown of the amino acid phenylalanine. Babies were born healthy but quickly developed a lifelong health condition with effects that were labelled, at the time, as “mental retardation.”

Today the stigmatizing and hurtful term is less often used. Instead, clinicians refer to learning delays or intellectual disability. But when the hospital staff said “PKU” to me on the phone, that’s how I’d been taught. And so that’s what I thought.

During genetics and psychology courses I’d learned that having PKU could mean childhood disabilities. That the condition led to developmental delays, mental illness, seizures and more.

That when a girl born with PKU grew up and tried to have children of her own she was more likely to lose the baby from miscarriage. Or to have a newborn with a very small head (microcephaly) who was also at higher risk for heart defects at birth.

From my own reading I knew that in too many families, no one had recognized PKU for what it really was. That sometimes a child lived out their life confined to an institution, painfully separated from their loved ones.

I’d read about renowned author Pearl Buck’s daughter’s condition which went undetected and led to lifelong disability. The first woman to win the Pulitzer, Pearl Buck also received a Nobel Prize in Literature for her popular novels.

Her historical fiction book The Good Earth about a Chinese farming family’s life story had been a bestseller in 1932. It was later made into an award-winning movie, and regained popularity once again after being chosen for Oprah’s Book Club in 2004. The classic story’s protagonist, a farmer, refers to his oldest daughter unkindly as “the poor fool” because she never develops mentally.

The author based the girl’s character on her experience with her own daughter. I’d read the book as a child after my Uncle, Donald Potter – who lived in China and taught English there – mailed it over intending that my mother would read it. He was distressed when he found out I’d read the very grown-up book instead.

In graduate school genetics classes I’d read another one of Pearl Buck’s important books. A heartbreaking memoir, The Child Who Never Grew shares her real-life experience with her daughter Carol. It became a classic in medical genetics studies.

Baby Carol had a PKU condition that went undiagnosed and so wasn’t treated. Her mother was a celebrated writer but Carol couldn’t speak or care for herself. No one knew why. Her mother reluctantly placed the little girl in an institution against her will, and in her memoir described the suffering that separation caused them both.

To me, the hospital phone call about my own daughter – and all that it implied – seemed surreal.

– excerpt from When the Baby Is Not OK: Hopes & Genes by Jennifer J. Brown, 2025.

Book Links:

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DT7MZ7YL

Apple: https://books.apple.com/us/book/when-the-baby-is-not-ok-hopes-genes/id6740871196

B&N: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/when-the-baby-is-not-ok-jennifer-j-brown/1146869011

Kobo: https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/when-the-baby-is-not-ok-hopes-genes

Bookbub: https://www.bookbub.com/books/when-the-baby-is-not-ok-hopes-genes-by-jennifer-j-brown

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/223703166-when-the-baby-is-not-ok